A lecture presented to the University of Oregon School of Music on April 14th, 2022.

Intro

It is a privilege to be speaking about a professional and personal issue which has shaped and defined my life and career. Musician’s Focal Dystonia affects 1 to 2% of musicians, regardless of them being professionals, amateurs, students, virtuosos, orchestral rank-and-files, famous or hopefuls.

This lecture is not only about doom and gloom. I am here, I am alive, I am playing the oboe, my career is prospering, I am making a difference in my life and in the life of others, I found use for my life within my dreams, and my future looks bright.

What is FD?

Dystonia is the 3rd most common movement disorder in the United States, affecting over 300,000 people. Dystonia is an involuntary muscle tension affecting both sides of a movement. As we play our instruments and utilize our fingers, the extensors and flexors in your arm play a game of cooperation which in my case gets disrupted by dystonia. Similarly, with embouchures, the play between opposite muscles guarantees the precision of our work, whereas embouchure dystonia prevents that balance from happening.

What we refer to as “playing one note” involves the precise positioning of dozens of muscles trained to precision through countless hours of practicing. The repeated work in practicing creates pathways linking diverse parts of the brain catering to what you see in the music score in front of you, how you hear it, how you react to it, the critical analysis of its proper performance, the emotions related to each moment, how and where this information is stored for future retrieval, and a host of other details, many of which escape our conscious perception.

Dystonia interferes with this process in ways that are still not completely understood. Dystonia changes how these pathways work, denying the proper function of the physical parts of our bodies.

“Focal” Dystonia, as the name indicates, is a localized dystonia, in a particular part of the body. And, “Musician’s” Focal Dystonia obviously refers to the kinds of situations when dystonia will affect us musicians, commonly separated into hand and embouchure dystonia. Focal Dystonia doesn’t affect only musicians, but also other people whose work involves fine motor skills, like surgeons, and writers for whom it is known as “writer’s cramp”.

The big questions are: how do we get Musician’s Focal Dystonia? What can we do to avoid getting it? And…once we fall prey to this ailment, how do we get rid of it? These questions all have the same answer: we don’t know. Guesses are not answers. Can we be cured? No, we can’t. However, some people claim to have been cured, and others - like me - claim to have found ways to live with it.

The diagnosis itself is questionable. There is no tell-tale sign of dystonia, no blood test, MRI, CAT scan or biopsy which can directly prove its existence within us. Diagnosis is done somewhat by process of elimination: we don’t have nerve damage, nerve entrapment, muscle this, tendon that, or other issues in a short list of possible explanations for our puzzling symptoms. Therefore, we conclude that focal dystonia is the most likely culprit.

In my case it took about three years from the onset of symptoms to the final diagnosis. And I confess to you that I was relieved when I was told I had fff—-ocal something. I had never heard of Focal Dystonia, so how bad could it be? We all knew that Leon Fleischer and Gary Grafman had “something”, but that is like saying that Itzhak Perlman had Polio: it’s there, we know, we see, we feel for them, we applaud their tenacity, but we never consider it could happen to us.

It is distressing that such a malady directly affecting musicians runs rampant through the music world and few people are talking about it. The Dystonia Medical Research Foundation offered instructive lectures to a few major conservatories, but they were summarily rejected. If we don’t know how it is acquired, nor how to fix it, it makes no sense to cause panic. Or so said the conservatories.

If 1 to 2% of musicians have it, it means that every orchestra has at least one, on average. I regularly receive inquiries from musicians with dystonia seeking guidance and I hereby open that door to any of you who might ever need someone to talk to.

In order to raise awareness I made the decision to not keep my case private. I figured it was best to lay it out in the open than to allow gossip to fill in the gaps. And it was about time we put this issue on top of the table for all to see. Since then, a new generation of doctors and patients has come around, diagnostics are now quicker, and therapies are multiplying, some with great success. However, due to the discrimination I have encountered along the way, I strongly recommended that if any of you ever develop Focal Dystonia or other medical issues please keep it private.

I am currently under treatment at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, paid for by your tax dollars, thank you, where I receive Botox injections. I also utilize splint gloves of my own manufacture which help me compensate for the effects of dystonia.

While there are some patients who have recovered, their success story is also clouded by little understood issues related to how serious they were affected in the first place. Some success stories involve particular circumstances which betray our ability to distribute that success to everyone affected by Musician’s Focal Dystonia. Our cheers for success stories are interrupted by the realization that not all fixes work for everyone, and the complexity of such "cures" often prevent every affected musician from obtaining the same results.

Studies, career

I became a professional musician at age 10, and by age 11 I decided I would do this for life. By age 13 I was soloing with orchestras away from home, and by age 15 I started recording. I majored not in oboe but in Composition and Conducting at the São Paulo State University, and then transferred to the Oberlin Conservatory so I could study oboe with James Caldwell.

Before I graduated from Oberlin I won an international competition in New York City which granted me recitals in Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston, a debut recital at the Weill Recital Hall and a solo performance with orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Other prizes came in Tokyo, Prague and the International Double-Reed Society.

By age 23 I had earned the coveted First Prize in the Geneva Competition, and by age 30 I was sitting

on the Principal Oboe chair of the Chicago Symphony. Four Grammy awards followed as a member of the orchestra, plus a separate one which still adorns my living room, for the recording of Richard Strauss’ Oboe Concerto with Daniel Barenboim conducting.

I worked under Pierre Boulez, and Sir Georg Solti. I heard Barenboim discussing Karajan’s

three secrets on how he made the Berlin Philharmonic sound the way it did.

I played the solo from Tchaik 4 accompanied by pianist Radu Lupu, and then at Carnegie Hall’s opening night. I was on stage when Rostropovich played Dvorak, and when Pollini played Brahms’ Second Concerto - soloists and works

whose recordings defined my teenage experience with music. Likewise with Alfred Brendel playing Beethoven’s 4th concerto. I recorded the Mozart Oboe Concerto live, with Christoph Eschenbach conducting.

I was there when 17-year-old Lang Lang played his debut with the Tchaikovsky Concerto. Maxim Vengerov was another late teen kid who loved to play ping-pong with us during rehearsal breaks. I was there when Peter Schreier led both Bach Passions.

I met and worked closely with giants like Principal Trumpet Bud Herseth and Principal Horn Dale Clevenger, who was also my carpool buddy. I was on the audition committee

which hired the incomparable Principal Flute Mathieu Dufour, and bassoonist David McGill. I lived in a beautiful house in one of Chicago’s most admired suburbs. My kids went to great schools. Life was beautiful.

Diagnosis

I started sensing symptoms of what eventually was diagnosed as focal dystonia three years prior to my seeing specialists about it. From the Chicago Symphony’s “tour doctor” I saw a neurologist at Rush Memorial Hospital, where two doctors concurred I had acquired focal dystonia.

Next came Northwestern Memorial Hospital where I met one of the world’s top experts in Performing Arts Medicine, Dr. Alice Branfonbrenner. She agreed it was musician’s focal dystonia, and laid down the law for me: I was destined to quit playing the oboe within a few years out of sheer frustration with what is an incurable, little understood neurological malady.

Next came the Cleveland Clinic where another world expert, Dr. Richard Lederman, confirmed the diagnosis.

I was stunned, and quickly realized my only channel to survival as a musician

was to go into denial. I respected and acknowledged my diagnosis, of course, but as long as doctors told me

“there is no cure on their end” I felt inclined to go look for it somewhere else. I tried acupuncturists, chiropractors, masseurs, Rolfing, and even an energy healer. I followed a theory that the mercury used in my dental fillings may have caused brain damage, I did an MRI searching for brain tumors, I had the common dental anesthesia Novocain injected into my fingers, I took steroids, and I took medicine for Parkinson’s disease as a doctor saw my situation as a form of paralysis. I saw a specialist in France, and did various natural therapies in China. I reached for help from the Musician’s with Dystonia group on the internet, whose page carried a warning right at the top telling us that if anyone had suicidal thoughts to call this number immediately.

I gradually gave up trying new therapies, because each and everyone of them carried a powerful promise: to return me to oboe playing. Surely it deserved my complete devotion with body, mind and soul. Invariably, after each failed attempt I fell into several weeks of depression. The day came when I had to factor in that depression before I engaged in a new therapy, and to this day I am very cautious and skeptical about big claims of a cure.

Losses

Alerting the Chicago Symphony’s management of my diagnosis was the professionally responsible thing to do. I could feel dystonia affecting my playing, and I didn’t want others to think I was being lax on practicing.

I divided my battleground into three areas:

Try to hold on to my job as long as possible while looking for therapies and medical solutions. As predicted by Dr. Alice Branfonbrenner, after 3 years of relentless trial and error I was unable to control two fingers of my left hand, even if my other 8 fingers were in top shape, as they are to this day. So I quit the Chicago Symphony.

Find something else to do with the skills and experience I had. Soon after my diagnosis sunk in I gave support to other dreams in life, including conducting, teaching, music administration and social work with music.

A gradual rehabilitation through retraining, which I am still doing to this day.

The next loss is the most terrifying one: my identity. Since before I was a teenager I had identified myself as a musician, and oboist. I spent my formative teenage years in the certainty of what I am doing with my life even as school colleagues struggled with self-assertion and career doubts. And all of a sudden all of this was gone. I felt a loss of identity, of self-worth, and couldn’t comprehend what exactly was my life’s purpose. I loss job, career, wife, kids, house, money, friends, colleagues, support structures, faith in society, trust in doctors, companionship, identity, self-worth, dignity and hope. The end result of such a monumental loss is to be expected, and hopefully understood. When we have nothing, we have nothing to live for.

What happened to me is the equivalent of death. It was as if I was outside of myself

watching life go on without me. Someone (the great oboist Eugene Isotov) eventually took my job in Chicago. I was spoken about, and eloquently, in the past tense. My children learned the difficult path of living without their father, one child went into drugs, and the other acquired severe illnesses linked to deep emotional distress. All my attempts to return to oboe were fruitless and all led to tendinitis as I forced my arm and fingers to do something they didn’t want to or didn't know how to do anymore. And that is how I hit bottom.

Diversification, splitting career

I looked into the lives of people who fought impossible odds, like Mahatma Gandhi, and of course Beethoven who acquired a major disability preventing him from doing the only thing he knew how to do. Gandhi was able to conquer his life dream of a free India, even though it didn’t occur quite exactly how he had hoped for.

And Beethoven showed me a prize: the 9th Symphony. In his agony, rejected and snubbed by society, beyond any possible hope to ever recover from his unexplained, incurable deafness, Beethoven wrote what became the most famous and most meaningful musical line ever created. There was a lesson in his example, a lesson which I humbly extend to all of you here.

Around that time the movie “Apollo 13” came out, and I again had my radar tuned to “how to confront impossible odds”. The flight director stated one phrase which was and still is key to my life and recovery: “what do we have in this spacecraft that is good?”. What did I have in my life, and playing, which I could still count on? I had 8 great fingers, I had a name, I had friends in high places, I had ideas, and I had hope. Later, on the same movie, when faced with the appearance of the worst disaster NASA had ever faced, the same flight director insisted that “this will be our finest hour”. With that in mind I learned to hang on by the cliché that the best is yet to come, even if at that particular moment I had no idea how or what that would entail.

I founded FEMUSC - Santa Catarina Music Festival, in 2006. It is through FEMUSC that I am here today, due to my association with University of Oregon piano professor Alexandre Dossin, who is also our FEMUSC piano professor. FEMUSC is now going to its 18th season, having served over 10,000 students from 40 countries. Our faculty come from some of the greatest music institutions in the planet, from the conservatories of Paris, Juilliard, Moscow and Royal College to the orchestras of Berlin, New York, Chicago and countless others.

Through FEMUSC we raised millions of dollars in funding from a “new” community for such events, bought a Steinway “D” from Hamburg, a Yamaha C7, bought cellos and basses so our students wouldn’t have to travel with their own, plus percussion and electronic equipment, and 17 harps, the largest ever order in the history of the Lyon&Healy factory in Chicago.

FEMUSC produces three times more economic activity than its budget and quickly became a postcard of its host city, Jaraguá do Sul, in southern Brazil. FEMUSC graduates now fill principal positions in top orchestras in the US such as the Seattle Symphony and the Metropolitan Opera, and nearly 100 graduates left the festival with scholarships to study abroad, including right here at the University of Oregon. FEMUSC proves that cultural events can and should be tools towards economic development, and not just a way to spend money.

I also founded PRIMA - Program of Social Inclusion through Music and the Arts, in one of the most needed places in an already needy country. We pinpointed the communities hardest hit with unemployment, drugs, violence and where government services were failing to make a difference, and we placed a youth symphony stack in the middle of it.

We spent over $3 million dollars on enough instruments, accessories, and music stands to fill 10 symphony orchestras. We developed and implemented a work philosophy whereby the notion of upper class, middle class and lower class was summarily eliminated as racist and counter-productive. We are all humans. Period. We worked with 4000 youth and children, never uttering a word against the local social perils like drugs, gangs, child prostitution, murders, and the sadistic way some parents would pay their drug debts, literally selling their children away. It was appalling to see our underage girls put on lipstick and make-up at the end of the afternoon as we finished classes, but one single word against these woes and we would arguably not return home that night. Plus, like it or not, that’s how they put food on the table. One day, as I left a particularly dangerous suburb, the army was going in. Not the police, the army. Students regularly mentioned gunfire at night. And of feeling hungry.

FEMUSC and PRIMA made my life beautiful again and gave it purpose. These institutions would not exist if I hadn’t acquired focal dystonia and left the Chicago Symphony. I thought

my life in Chicago was perfect and beautiful, but it is incomparably more beautiful and complete now. Perhaps Chicago’s life was more selfish, with more creature comforts and personal recognition, but I confess to you that no such comforts can warm the heart like your knowing that your presence in this world has made a difference for the better in another human being's life.

Road to recovery

My life and career became divided between my socially conscious activities at FEMUSC, PRIMA and other ventures, and my resilience towards oboe playing. I gradually made advances in treatments and coping strategies against Focal Dystonia. In my worst year, less than 10 years ago, I opened my oboe case only on two occasions during the entire year.

I initially glued coins and other extensions to my oboe, hoping to transform the instrument into a more ergonomic and functional unit carefully adapted to my fingers. That is called a “sensory trick” because it tricks the brain into thinking I am not actually playing the oboe, but something else, like a saxophone. The ergonomic oboe allowed me to practice and play for more hours and thus to gradually regain my performance ability. I eventually settled on only one bridge, which was a coin added to the ring finger. That coin came off and went back on a few times as I attempted new treatments and ideas.

Discrimination

There were physical challenges, but one would not think discrimination would be high on the list of challenges we endure as victims of Musician’s Focal Dystonia. I may “look white”, and no doubt over the years benefitted from being a white male in situations where I met those who exercised their prejudice on my behalf. On the other hand I am also latino, and grew accustomed to encountering racism and dismissal due to my particular ethnic background. As a person with disability, though, I encountered the most shocking

behaviors. People who judge us do not see our potential. We are seen as invalids, as shadows of our past, and as people undeserving of a second chance.

We are judged not by how we strive to conquer our limitations - and succeed at it, but according to how the observers think they would fair if they were in our shoes. Trouble is, those observers have no sensitivity training nor have they any idea what it feels like to look at the world from our window. From my point of view, people who are on wheelchairs are heroes. And so are the blind. How can they possibly survive, and thrive, in this society? And no, building a wheelchair ramp does not signify that that person will now experience equality, not when society looks upon us as losers just for existing. But we are not losers. We are not invalids. We are just unique, and we don’t want to give up our fight to be treated as equals.

Chicago

The THIRD strategy in my conquering the effects of Musician’s Focal Dystonia was my rehabilitation as an oboist. It was only five years ago that I successfully re-auditioned for my old position with the Chicago Symphony. I received a hero’s welcome from Maestro Riccardo Muti, my old colleagues, the public, management and the local media. In just a few months I was invited to speak on four occasions to donors, governors, and even on the all-important Annual Meeting of the Board of Trustees, telling my story of overcoming the effects of focal dystonia. I also took the opportunity to clarify my situation to the media on several occasions, including an in-depth exposé of focal dystonia for Chicago Magazine which has become central to describing what it is and what we go through as musicians with dystonia ( https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/february-2017/oboe-alex-klein/ ).

A few months into my return to the Chicago Symphony I was asked to change my equipment, specifically my reeds. The Audition Committee felt they should change to accommodate a different sound and way of playing. In the process, they inadvertently interfered with my protocols in regards to focal dystonia, as well as with my ongoing process of adaptation into the orchestra. I immediately alerted the orchestra’s management that this was not appropriate, as they essentially asked me to give up my "proverbial wheelchair". I was, after all, a musician with a disability requiring careful processes of adaptation to playing, and to playing within the orchestra, a situation that is more sensitive than a normal case of pre-tenure adaptation. The comparison has limitations. An oboe reed is not directly linked to my disability like a wheelchair is linked to movement, but it happens to be a central part to my package of adjustments which allows me to play, being a go-between between my dystonic limitations and the requirements for playing the oboe.

As reed makers, oboe players adjust their reeds so as to meet their musical needs

for projection, effort, tension, articulation, blending and of course personal taste. And, as persons of disability we rely on the same equipment to regulate how much tension we apply in order to play, in a delicate balance between playing needs and the body's ability to supply those needs. If we are able to meet all playing needs we can call ourselves "cured", and if we aren't able to meet those criteria we might as well quit because....we "can't do it". But what about those of us who are in the middle of the road in this debacle? We can meet those criteria, but only if we are able to utilize assistance from our specialized and personalized equipment, or a package of equipment, rest and other strategies - strategies which were clearly delineated in the Chicago Magazine article. The playing tension must be very carefully managed because focal dystonia allows me only

a limited window for successful oboe playing. And by "successful oboe playing" I refer to the ability to play at a level where all standards are met and listeners aren't able to pinpoint the presence of a disability. If I apply too much tension, or too little, I run the risk of destabilizing the careful balance that exists between my muscles and the limited instruction they still receive from my brain. And even that is already within the realms of miracles and improbabilities. I can’t change my equipment without directly affecting how my disability is manifested in my playing. My equipment, my reeds, are my wheelchair, my cane, my hearing aid. These requirements are similar if not identical to those expected of any musician being considered for tenure in an orchestra. All of us, independently of the presence of a disability, must strive to meet the same standards. It just so happens that some of us have a rockier road ahead of us, and we count on the idea of fairness and understanding of an able-bodied world to give us a chance to prove ourselves. For that we need time. And time was taken away.

Changing my equipment is akin to creating unfair and unethical circumstances leading to a disabled person tripping. It wouldn't be different than asking any other musician to adopt artificial tensions unbecoming of their instruments' techniques - say, by adding rubber bands between their fingers - and

then compelling them to step on stage under the expectation that they would play at their very best. This would be unreasonable, cruel and a bit cowardly. This can't happen, one would think, to ask the blind to see, to ask the wheelchair bound to stand up and walk, nor to ask a musician with dystonia to let go of their pre-assigned playing scheme and somehow produce music without it. It put me in a situation so as to unnecessarily prove myself beyond a reasonable expectation, to prove that I am not disabled, to prove that focal dystonia for all intents and purposes doesn't exist, or have no effect on my playing. Or perhaps it is a symptom of a strong desire of the organization to not maintain peoples with disabilities among its ranks - a guess calculated upon matching the percentage of employees with disabilities measured against the US Census and the percentage of disabilities in the general population. As a society we have grown used to using such Census comparisons to raise questions about the presence of women and afro-descendants in orchestras, working steadily towards a proper level of representation which recognizes the multiplicity of genders, races and cultures in society. That representation is grossly out of balance when it comes to the presence of peoples with disabilities in symphony orchestras. It leaves us with the clear impression that in front of major US symphony orchestras lies a not-so-subtle message saying that "musicians with disabilities may not apply".

A few weeks after the request that I change equipment, the Chicago Magazine released the article detailing my routine as a musicians with focal dystonia (https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/february-2017/oboe-alex-klein/). Soon thereafter I was summoned for a meeting….not with the Audition Committee, nor with the Music Director, but…with the CEO of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Jeff Alexander. I was then informed that my tenure proceedings have been suspended. What was supposed to be a two-year adaptation period lasted approximately 6 months - incomparable even with interrupted proceedings with able-bodied musicians. From that day on I was not allowed to play a single note with the Chicago Symphony. My dismissal was immediate and lasting.

I was devastated, of course, and this situation took several steps back in my recovery. I once again lost my sense of identity, purpose in life, and self-worth. I was again without a job, without an ability to care for myself or my family. I sold several instruments in order to support our immediate needs. In the ensuing months lost 40lbs/20kg, and probably would have lost more, or died, if I had not moved to Canada and acquired access to healthcare.

Canada and Calgary

Two separate lines of thinking led me to consider moving to Canada where I successfully auditioned for the Principal chair with the Calgary Philharmonic. On one end was my family’s circumstances, being latinamerican during a time when even “legal” immigrants from our part of the American continent are vilified, often with deadly consequences. Canada permits the families of its foreign workers to live together, whereas that is not possible for US permanent residents like myself, particularly latinos - not without enduring several years of delays and separation which would have costed me the childhood of my young children. The other factor of course was the tenure proceedings, as Canadian orchestras offer exactly the same pre-tenure period of adjustment to both disabled and able-bodied musicians, treating those of us with disabilities with the same identical opportunities as anyone else. In my experience, what happened in Chicago, where the tenure proceedings for a musician with a disability are significantly different than that applied to able-bodied musicians, does not happen in Canada.

Future

It has been rough living with Musician's Focal Dystonia and beating the odds, but I count my blessings. True, I still have Dystonia and its effects on two fingers of my left hand have remained unchanged over the past two decades.

However, over the years I found ways to cope, and I continue to look for new information, new treatments, and experiment with new strategies, just as long as they don't bring with them excessive promises likely to cause severe depression if they fail. I am using a splint glove of my own manufacture, which counters the effects of focal dystonia on my fingers. If dystonia positions my ring finger one inch below normal, I can have a splint hold it one inch higher. Similarly, if my middle finger is repositioned a half-inch higher by dystonia, I can have a wire holding the finger down by the same amount and strength. This experiment brings my fingers closer to “normal” and have proven worthy. With this splint glove I trust myself more, and am less afraid of muscle spasms. The overall result is that I can be freer to express myself as a musician and focus on artistic matters rather than constantly focus on the probability of my fingers remaining under control.

As mentioned before, I continue taking regular treatments of botulinum toxin - Botox - at the National Institutes of Health near Washington, DC. Botulinum is a dangerous poison which is applied in minute quantities specifically on the part of the muscle which can cause my fingers to return to their original positions. I am no longer General Director of PRIMA, which I quit in order to return to the Chicago Symphony in 2016, but I continue to work as Artistic Director of FEMUSC. Moreover, my team and I are launching two new ventures this Summer. These will be music festivals attached to social programs, essentially mixing the principles of FEMUSC and PRIMA together. At each venture we will hold an annual music festival where we celebrate music and our ability to turn music into social development. Each festival and its patrons will raise enough funds to sustain a year-long social program in that city, teaching citizenship through music, favoring the underserved communities around them.

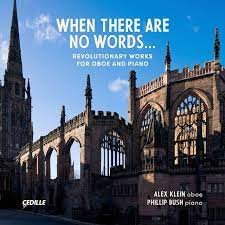

I continue to record and am humbled by the rave reviews these projects are receiving. During my latest exit from the Chicago Symphony I recorded "20th-century Sonatas" for Cedille Records, which was nominated for a Grammy Award for “Producer of the Year”, together with other projects showcasing Cedille Records founder and President, Jim Ginsburg. And now, in 2022, we have just released the anti-war recording project “When There Are No Words” I am on track to finish two more CDs by the end of this year, one of oboe+harp works with harpist Rita Costanzi, and the other of virtuoso works including Paganini Caprices and Pasculli's Three Characteristic Studies (of which "Le Api" is one). Recordings are what is left of my solo performance career. The performances I would have made if it weren't for focal dystonia can still be immortalized through recordings.

I have also started editing publications and will soon be releasing two books of Bach Studies through Theodore Presser in Philadelphia.

And as for playing on uncomfortable equipment, even though I was asked to play on

different reeds, sound and uncomfortable levels of tension for my particular situation, I immediately went on an European Tour with the Chicago Symphony and even received a glowing review (https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/la-scala-ritrova-maestro-AEYIV8E?refresh_ce=1) from that particular tour’s most expected concert: the return of Riccardo Muti to La Scala in Milan after a 10-year absence. Only the names of maestro Muti and mine were mentioned in that review which was then endorsed by and submitted to the entire organization by the Chicago Symphony management. That is to say, the challenges of playing without my primary equipment were met, with flying colors. It is hard, but it can be done.

Summary

For all of this, may I be the bearer of bad news for a moment: life brings unexpected bad news to everyone. I am not alone, though hopefully I will be the only one on this room to have to endure Musician’s Focal Dystonia and its consequences. But dystonia is not the only storm out there. I beg all of you, therefore, to be brave. Be strong.

It’s not over till it's all over.

Your best - in everything - is always ahead of you.

Create and maintain a good support structure around you, at all times, for good and bad times. Do realize that, sadly, we seem to have more friends when we are well, and many such "friends" will disappear when your life enters difficulties or disease. Learn to identify who are your true lasting friends.

Eventual bad news may be a certainty - after all, we will all die at some point, but you need not be caught by surprise. Be ready. Be in the knowledge so you can attenuate the consequences when they come.

In every occasion, but certainly once you have your job, consider working towards inclusion. Treat everyone equally, regardless or their gender, sexual orientation, national origin, disability status and so many other reasons society imposes strife on people. Be a force for good by investing in human potential, and not in bigotry or prejudice. The future will thank you for that.

Enjoy what you have now. Play your heart out. Walk on stage as if this is your one and only time ever, because nothing beats the now in our lives.

Thank you.

The End.

Comments